I will never tired of etymology.

I've said many times that dissecting words was one of the most important things I've ever learned. And it's something that my interest in language led me to do on my own. No one taught me, and that's a damn shame.

I have many multi-lingual friends. I have a friend who speaks five languages, including one I'd never even heard of, which happened to be her first. I have another friend who, over the course of her life, has practically collected languages: Armenian, Arabic, Russian, Turkish... I can't remember them all. I have friends who are ASL interpreters. Friends who teach French, Spanish, Chinese. And, although I have no scientific research to back this up, my guess is that most non-Americans in the world speak at least two languages.

Then there are languages of vocation that are complete mysteries to me. I have a friend who's a midwife. Sometimes I send her screengrabs of my medical test results, so she can explain them to me. Another friend is a neurologist. Another has a PhD in geology. I mean, jeez, I barely passed my geology class in college, and do you know why? Because they're ROCKS, man. I can't tell the difference. But Adam is a DOCTOR, of ROCKS. Totally different language there.

|

Pictured: How I learned that showing up, every morning, to an 8:00 am college science class can

earn you a grade that your test scores would deem completely impossible.

|

I speak Theater. It's a language spoken by most of my friends, at least conversationally. We all understand "flies" and "upstage" and "FOH" and "call times." We know "Thank you, five" and "Q2Q" and "curtain speech" and "call board." We understand what someone means when they describe something as "Brechtian" and we know that "absurd" is not the equivalent of "weird." Some will converse at length about Artaud and Boal and Heathcote.

I get frustrated when people who don't speak Theater assume they understand anyway. Kind of like when Archie Bunker put an "o" at the end of words so Spanish-speaking people could "understand" him.

| ARCHIE BUNKER: Hey, good boy, Pedro. HECTOR ELIZONDO: I am not a boy. I am a man. And my name is Carlos. ARCHIE BUNKER: "Carlos" it is, Pedro. |

Case in point: Last year, at school, I decided that our spring production would be two one-acts. Because directing two one-act plays would be the time/effort-equivalent of directing one two-act play, right?

Sooooo not right.

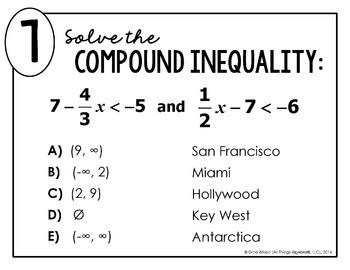

|

| Kind of like how four warm-weather American cities are equal to one frozen continent...? |

It's directing two plays, at the same time. As it turs out, the length of the material doesn't matter, because each play is completely different in every way except length: directorial concept, tech (props, costume, set, lighting, sound) design, cast, pacing, genre... everything. Including, I discovered, language.

Each play, each production, each cast, and each cast member has a different language. I've recently discovered this, and that if I'm not open to learning the new language of each new set of circumstances, it leads to misunderstanding, frustration, and resentment.

At school this past spring, I directed The Laramie Project. I knew it would be tough, emotionally, physically, and every other way. I was right about that.

But I didn't expect the language barrier. Not with the cast, but with the process.

The Laramie Project has about 80 characters in it. It's written for eight actors. We had eleven in our production. (Kansas City Academy is a very small school.) That means everyone played 6-8 characters. Tricky for them. What was unexpected for me, as I was blocking (writing down where everyone moves onstage) it, was keeping track of 80-ish characters at all times. Writing blocking for eleven actors? No problem. Writing blocking for 80 characters, most of which are invisible at any given time? Lots of problems.

I had to figure out ways to record "where we left the character" onstage, as most of them are recurring, and so had different costume pieces or props, which would be left behind as the actor crossed the stage to "pick up" a different character.

|

How much sense does this make?

|

Is it at least better than this?

Because they say the same thing.

|

And so on. But that example was just Jeffrey, and three of his characters. Now multiply that by eleven actors and 80 characters. (That math doesn't actually work out, but you get the point.)

So, I had to develop an entirely new language, for me at least, to figure out where actors were, which was different from where characters were, how to move them all around the theater, and how to communicate all this to the cast, many of whom had never been onstage before.

I won't go into details, just know that the whole thing gave me a brain ache.

But wait! There's more! Because this was basically all for me. What about the actors themselves?

First, not all actors were in the habit of actually coming to every rehearsal that they were called to. (Responsibility and accountability are things a lot of adults haven't even learned.) So I had to use place-keepers, so everyone who actually showed up to rehearsal could keep track of where a missing actor was supposed to be.

So, stuffed animals with actors' initials. Yup.

|

Seen here: My prayer that fewer than five actors would be gone at any given time.

|

|

| The role of "Jen" in tonight's rehearsal will be played by Creamcheese Containerlid. |

The actor could pick up, say a Triscuit box, which represented their current character, and would know exactly where that character was "left" at all times, and so could know where they had to be onstage before that character appeared again. Oy.

So that's my phrasebook for Laramiese.

The language of The Man in My Beard (AKA The Ballad of Frank Allen, by Shane Adamczak), the show we presented at this year's KC Fringe Festival, was completely different. Because duh. Different show, different language.

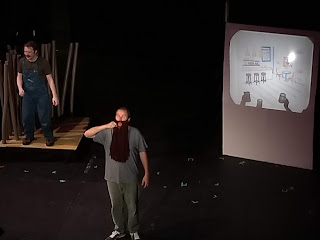

|

J. Will Fritz and Bob Linebarger

Photo: Crawford

|

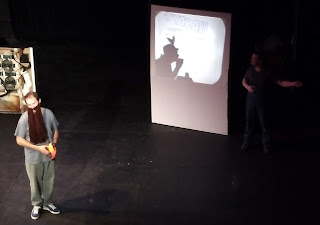

|

Bob Linebarger and J. Will Fritz

Photo: Crawford

|

|

Did I mention that there were songs too? Yeah, songs too.

Photo: Crawford

|

Part of the necessity for the invention of a new language here was the fact that I cast four people in a two-man show. The play was written for a bare stage, but I had this awesome (?) idea that we could enhance the story with the use of projections and shadow-play. So I cast two people to pretty much live behind an onstage screen for the entire show.

|

| You know what they say: Three hands, warm heart. |

"This won't be confusing at all," or anything remotely similar to this, is not even close to any thought I ever had, before actually starting rehearsal.

First, in addition to Bob and J. Will, who were seen during the whole play, I had to block people who weren't actually onstage, and yet, they were an integral part of the production and had to do stuff to keep the show moving. But I couldn't see behind the screen to know who would be doing what, so I couldn't write that "Jill does this" and "Natalee does that" with any knowledge of that actually being possible. So, I ended up writing "SFX" (how the kids these days spell "special effects") does this and that. Easy enough. Except...

There were many different types of effects: transparencies for the Olde Tyme overhead projector, shadow acting, and sound effects. So, the titles "SFX: TRANS," "SFX: SHADOWS," and "SFX: SOUND" started appearing all over my copy of the script.

|

SFX: TRANS + SFX: SHADOWS:

Bob and Jill Gillespie's shadow, out to dinner. Also, slight political barb.

|

|

SFX: TRANS + SFX: SHADOWS:

Bob, Natalee Merola as "Old Lady in Hat at the Bakery," J. Will

|

These. Two. Simultaneous. Shows.

They're onstage at the same time, but the show in front of the screen and the show behind the screen are very, very different. They're dependent on each other. They interact with each other. They cue each other. But they're not the same play. They're two halves of a whole. But they're still separate, with very disparate needs and I had to figure out how to talk to them both, at the same time, in two distinct languages.

How, at this stage of my career, do I still not realize what I'm getting myself into? Me and my bright ideas. Rushing headlong into a potential theatrical imbroglio.

And then, figuring it out. Or at least, trying to. Maybe that's the whole point. If I really knew what I was getting into, I might avoid doing it.

I don't feel like I dream big. I do, at times, dream weird. I dream in color. I dream in language.